MISSION

Created in 2008 in Charlotte, NC, the Classic Black Cinema Series (C.B.C.S.) has been specifically designed as a vehicle to expose the community to the vast artistic value black film has had around the globe throughout the years.

The series showcases the amazing diversity of cultures and experiences that are woven within the African Diaspora through a selection of films.

Our mission is to appeal to as diverse a population as possible and further the appreciation of Black Cinema. We aim to not only draw a diverse group of movie goers together, but also to provide a forum for Charlotte area residents to openly discuss social issues and the unique legacy of black filmmaking that has served as a frame of reference for today’s contemporary films.

The films explore common themes that run through black films that are influenced by black culture in itself.The love of movies is cross-cultural and we seek to take advantage of this universal pastime to provide a cultural bridge in our community.

LOCATION:

harvey b. gantt center

551 S. Tryon St.

Charlotte, NC 28202

COST:

FREE FOR GANTT CENTER MEMBERS OR $9.00 WITH REGULAR MUSEUM ADMISSION

upcoming screenings

Each month we showcase the amazing diversity of cultures and experiences that are woven within the African Diaspora through a selection of films. We are diligent about selecting films that interest and reflect the artistic contribution that black culture has had in the world and foster relevant, topical, compelling and even challenging discussion among our audience.

Our movies screen every 2nd Sunday of the month

January

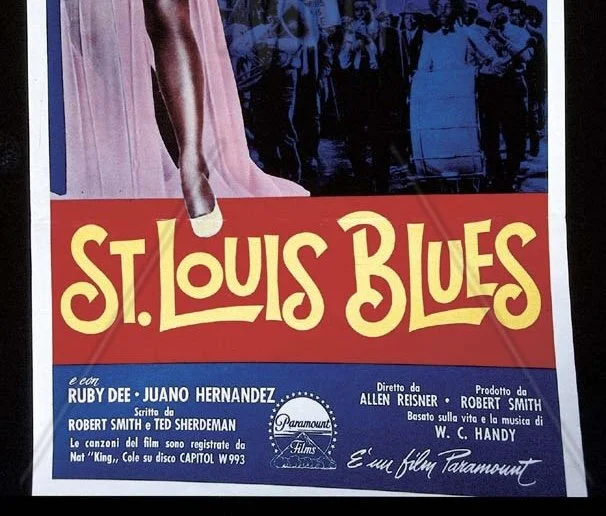

ST LOUIS BLUES

A biographical film on composer and musician Will C. Handy (Cole), who is considered the Father of the Blues. Will’s father is a pastor who belives any music outside of hymns is devil-worshipping music. Nevertheless, Will is drawn to writing and performing secular music, which causes a divide between he and his father. As Will becomes successful, he is torn between his success and losing his family.

February

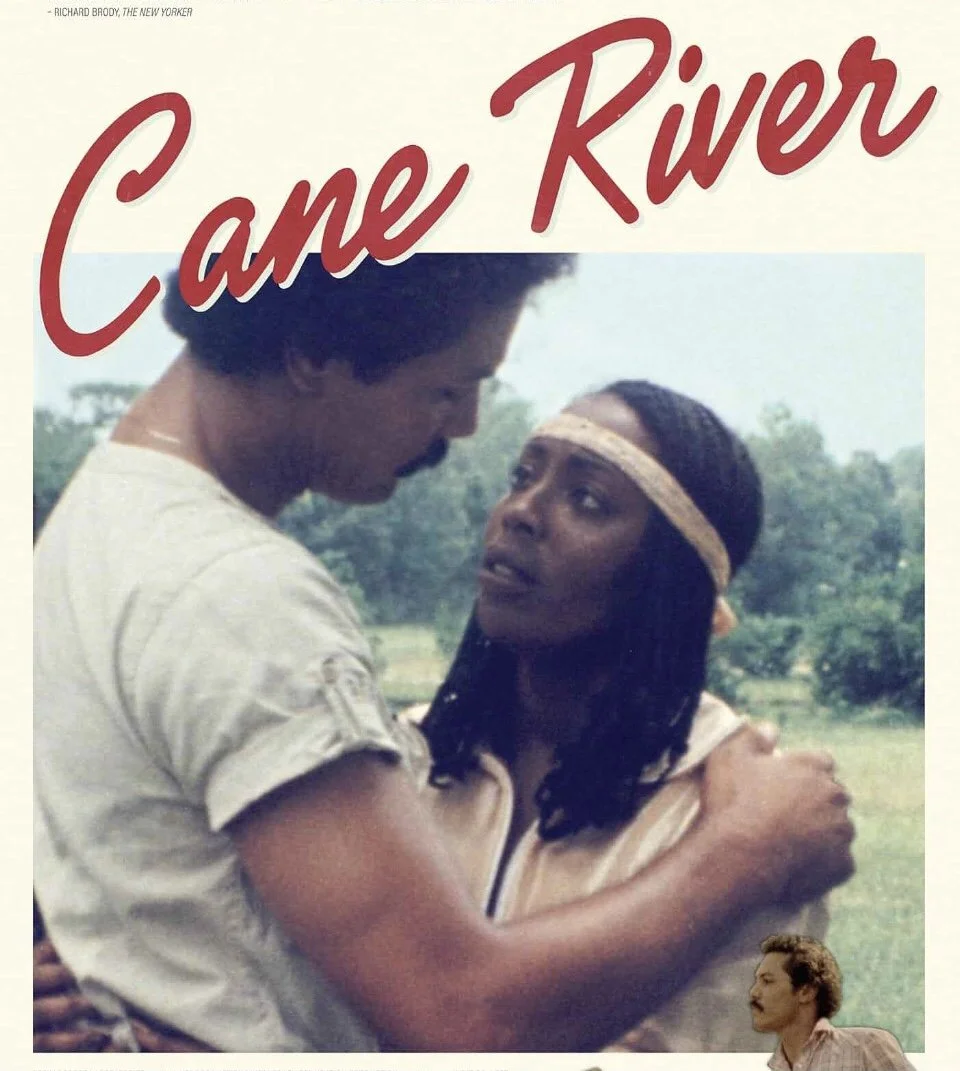

CANE RIVER

Late filmmaker Horace B. Jenkins’ early eighties African-American film Cane River epitomizes the smooth, but potently observational, character study of black division and togetherness — all under the complicated umbrella of love, cultural traditions and biased Southern class self-identification. Rich in resonance and thoroughly revealing in its absolute truth, writer-director Jenkins delivered an absorbing black romancer that delves into the psyche of blackness and belonging.

March

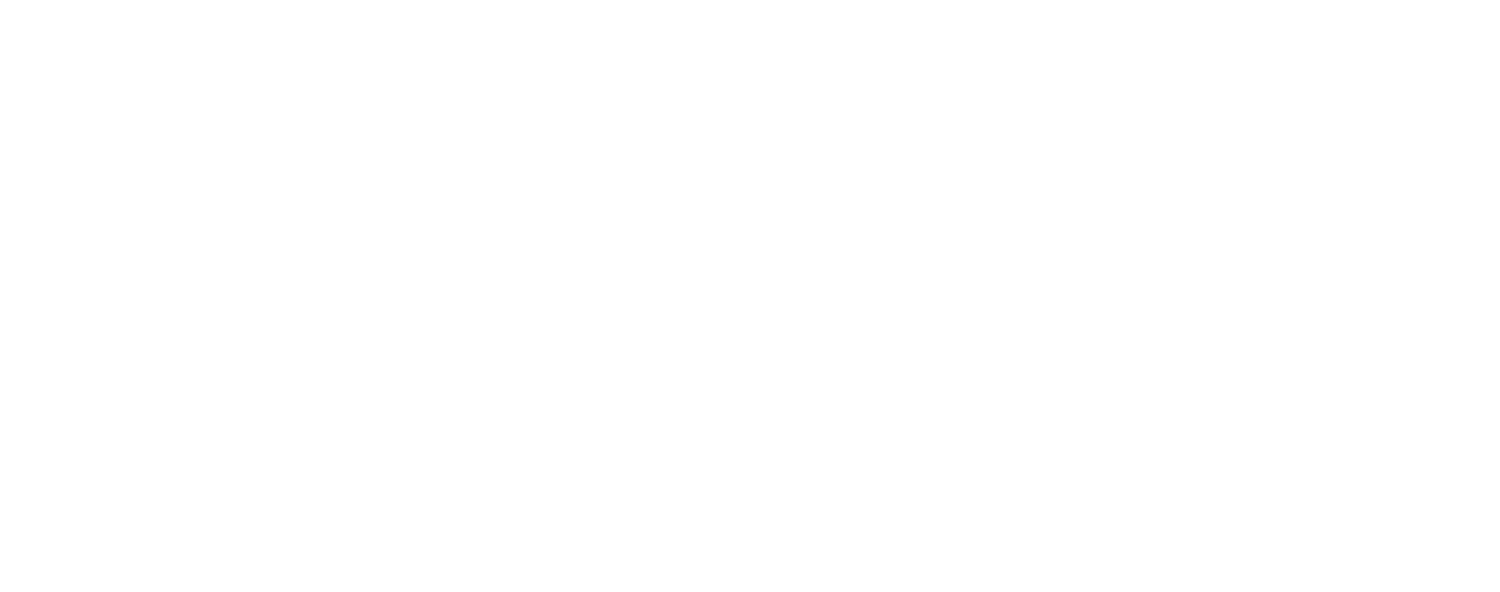

NEW ORLEANS

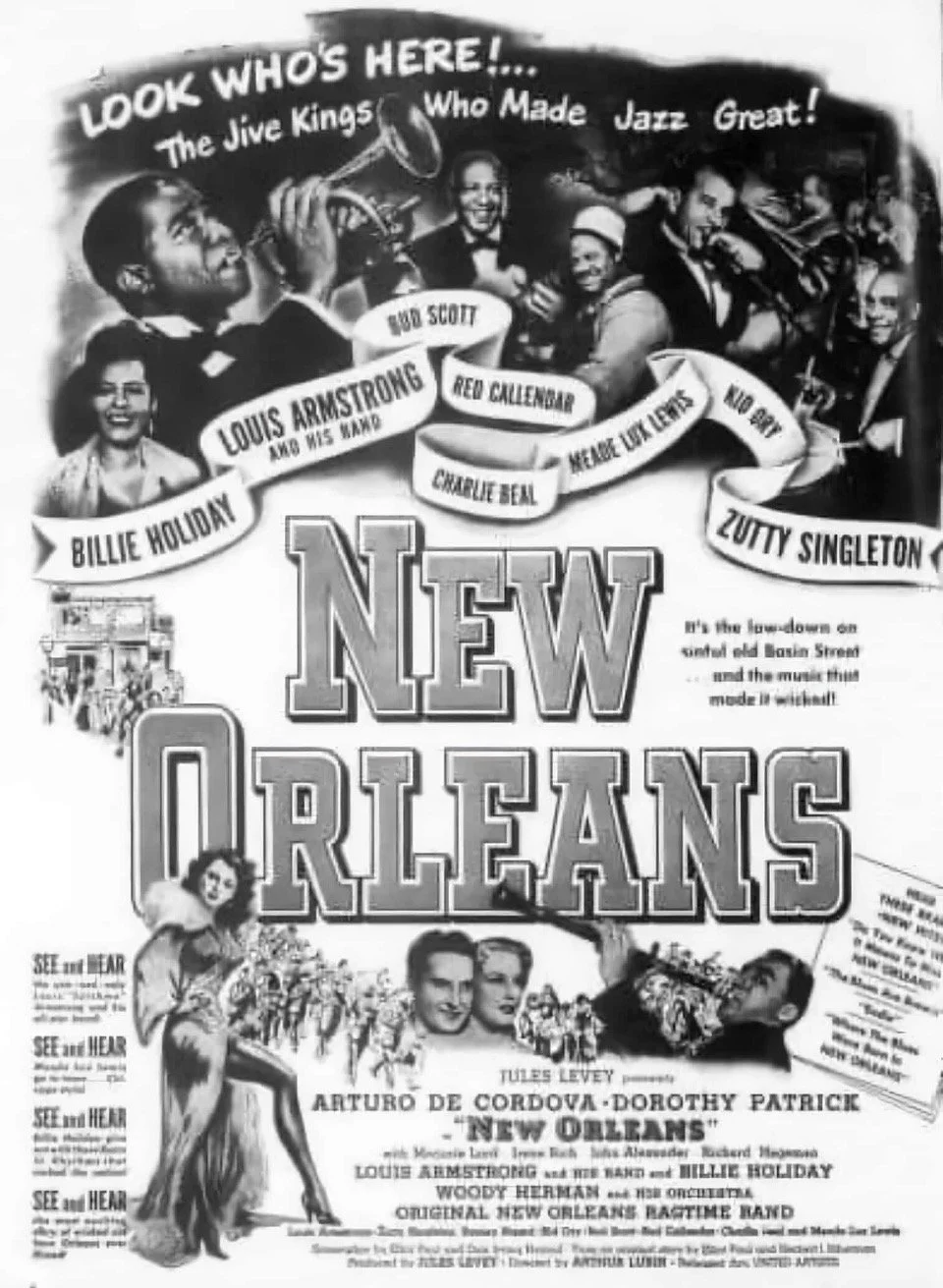

A gambling hall owner relocates from New Orleans to Chicago and entertains his patrons with hot jazz by Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Woody Herman, and others.

April

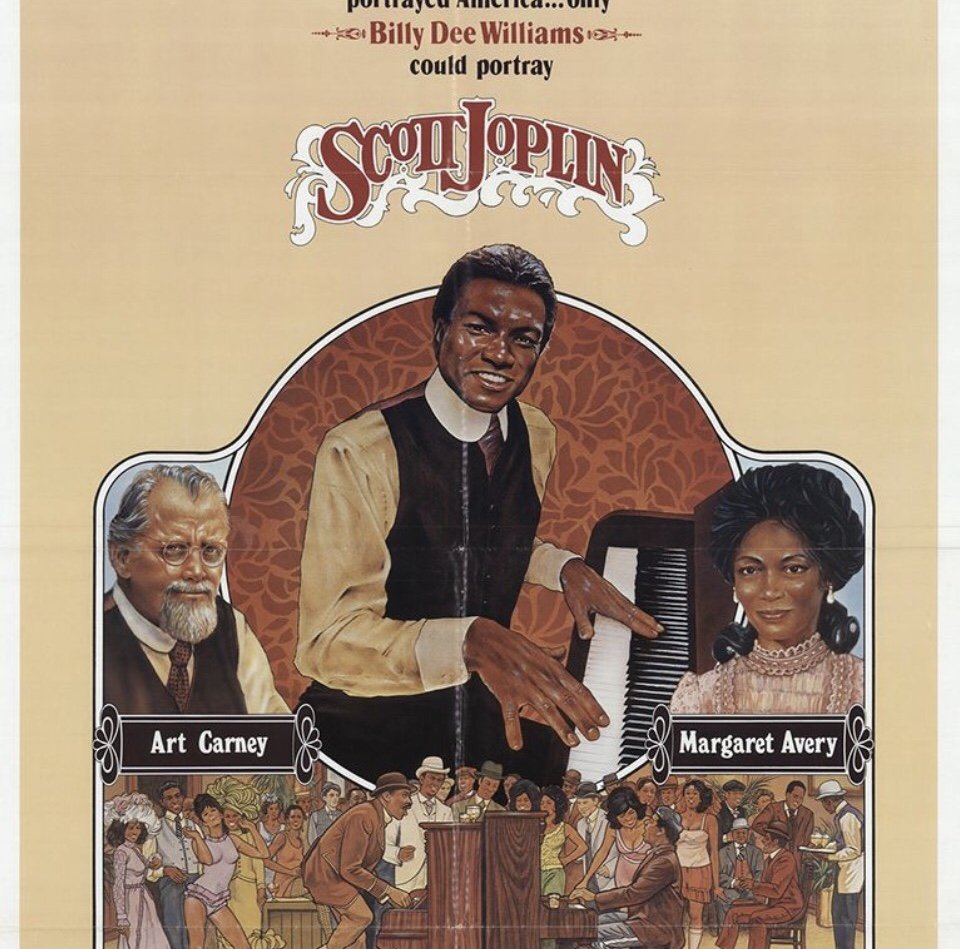

SCOTT JOPLIN

Details the life story of Scott Joplin and how he became the greatest ragtime composer of all time.

May

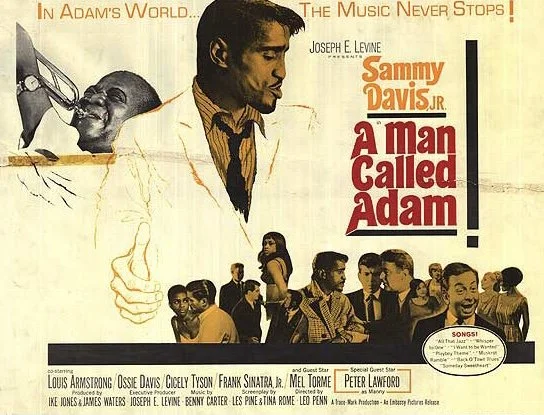

A MAN CALLED ADAM

Legendary entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. (Anna Lucasta) headlines a star-studded cast including Louis Armstrong (Paris Blues), Ossie Davis (Jungle Fever), Cicely Tyson (Bustin’ Loose), in this powerful drama about a jazz musician who “has it all”—love, friendship and fame—but whose tormented past threatens to destroy him and his career. Beautifully shot in stunning black-and-white.

June

SWEET LOVE, BITTER

A gritty, convincing, and downbeat portrait of one man's self-destruction. Using the tragic story of Charlie Parker as its blueprint, it documents the last days in the life of Richie Stokes, a brilliant, yet addicted and aimless black saxophone player. A somber, sad, and reflective affair, full of affecting performances and a jazzy score.

August

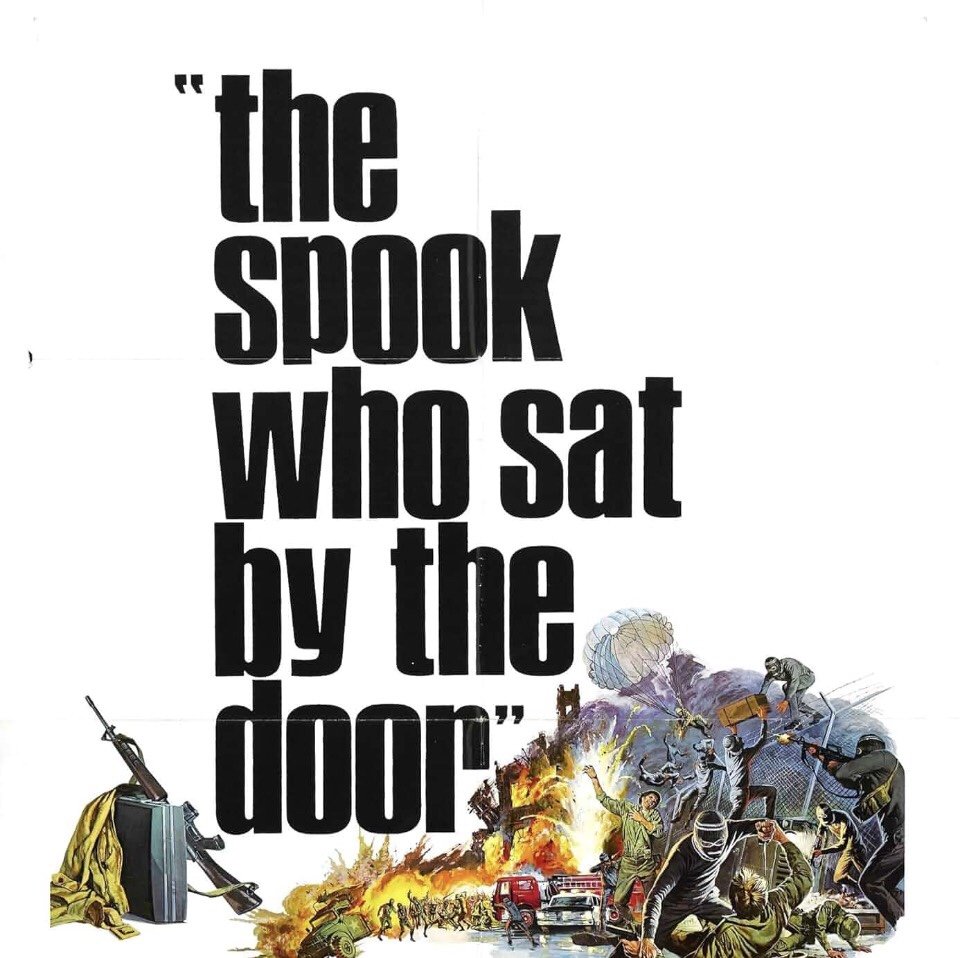

THE SPOOK WHO SAT BY THE DOOR

Based on Sam Greenlee’s 1969 novel, “The Spook Who Sat by the Door” is an explorative, calculated adaptation. The Chicago-set story, directed by Ivan Dixon, is amplified by a clever, witty, inspirational script, suave ’70s fashion, and tactful action-forward sequences. At the onset of the film, we witness the superficial efforts of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to become more diverse after a politician runs on the basis that the CIA is exclusionary to boost the Black vote in his favor. As the CIA attempts to avert these claims, they enlist just one Black agent. From the onset of the film, it’s unequivocally clear that those in power care only about the optics; there are no true allies on the inside.

September

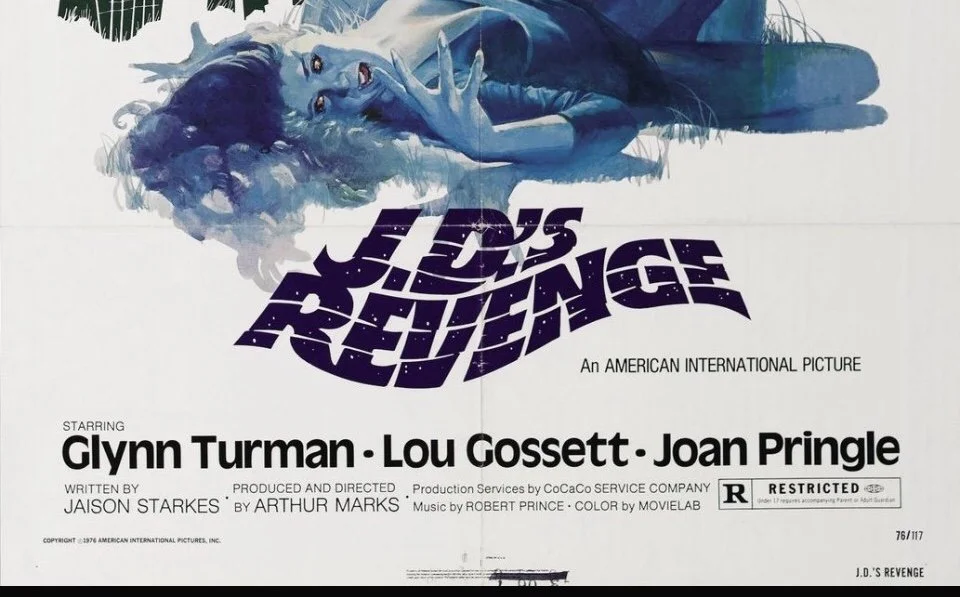

J D’s REVENGE

Murdered on Bourbon Street in 1942 New Orleans, a gangster returns from the dead 34 years later possessing the body of a young, black law student in his quest for revenge.

October

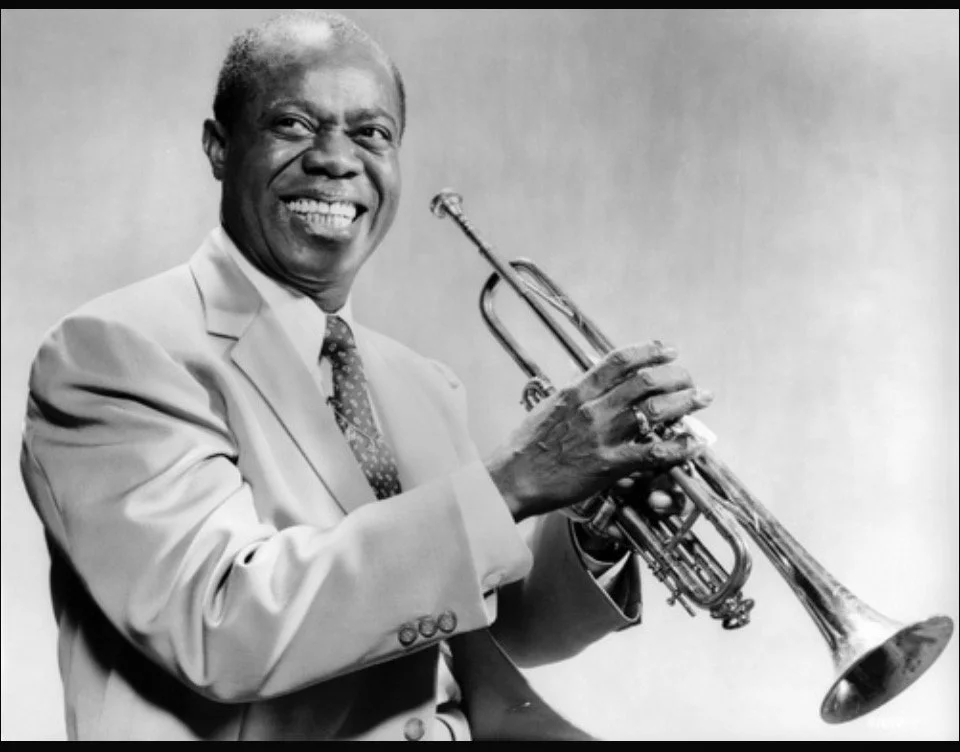

ABBY

A marriage counselor becomes possessed by a demon of sexuality when her father-in-law, an archaeologist and an exorcist, accidentally frees it while in Africa.

November

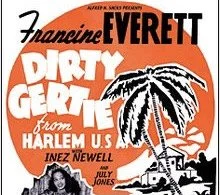

DIRTY GRETIE FROM HARLEM USA

An all-black Caribbean island resort welcomes flashy dancer Gertie La Rue, forced to perform in this remote spot because she two-timed Al, her Harlem lover and backer, once too often. As Gertie amuses herself by dazzling the local men with her sex appeal, sanctimonious Mr. Christian (shades of 'Rain') schemes to either reform her or have her thrown off the island. On opening night, her sensuous performance exceeds Christian's worst fears...but more serious trouble awaits.

December

BLACK ORPHEUS

In the heady atmosphere of Rio's carnival, two people meet and fall in love. Eurydice, a country girl, has run away from home to avoid a man who arrived at her her looking for her. She is convinced that he was going to kill her. She arrives in Rio to stay with her cousin Serafina. Orfeo works as a tram conductor and is engaged to Mira - as far as Mira is concerned anyways. As Eurydice and Orpheus get to know one another they fall deeply in love. Mira is mad with jealousy and when Eurydice disappears, Orfeo sets out to find her.

About

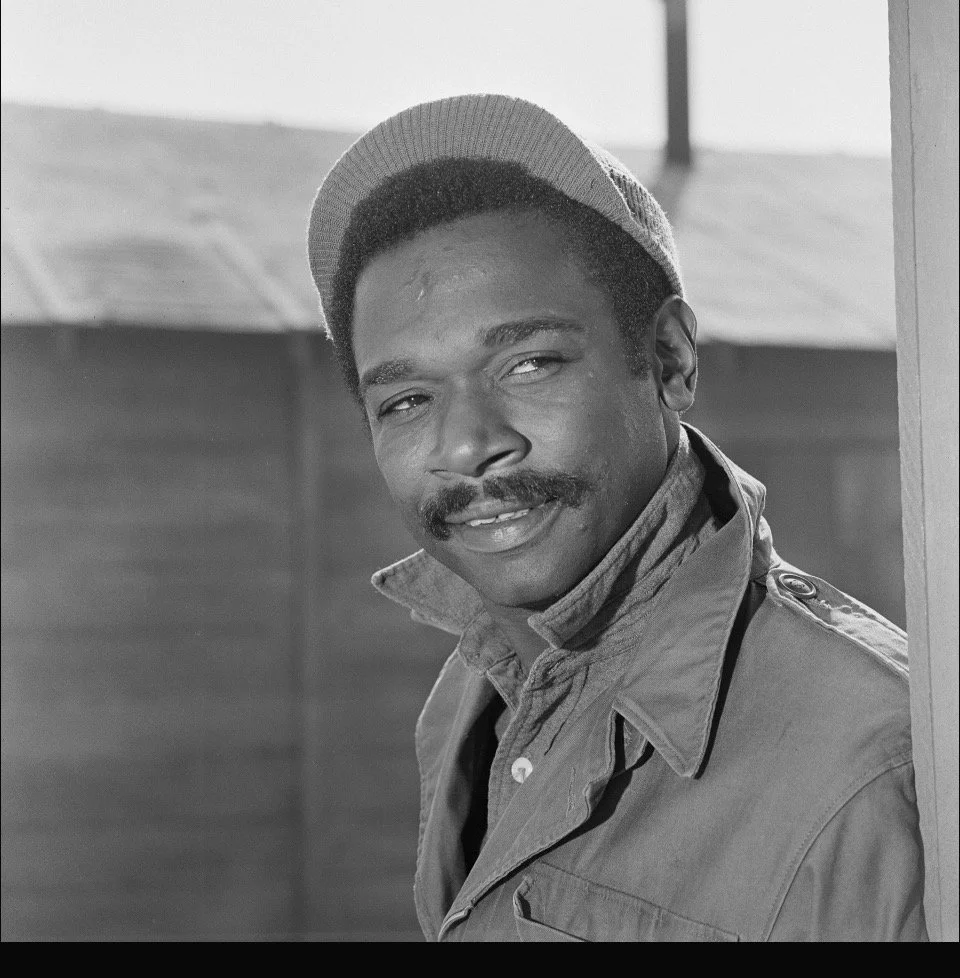

CURATOR AND HOST: Felix curtis

After retiring from a long career as a computer systems analyst, Felix came to Charlotte in 2006 from the Oakland / San Francisco Bay Area. Being an avid film buff and historian Felix started sharing his passion with the public as a curator of “The San Francisco Black Film Festival” and “Black Filmworks” the annual film festival component of the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame where he later served as Executive Director.

Felix was actively involved with Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame for over 12 years, however, he was a participant in their activities since it’s inception 28 years ago.

His first involvement with the organization was as a ‘Community” level judge for the Film, Video and Screenplay Competition. This was his first exposure to the collective works of independent Black filmmakers. Felix was enthralled and fascinated by the works and took it upon himself to get more involved by enhancing the processes of judging and presentation. He coordinated the annual Film and Video Competition for over 7 years which involved a review of all films submitted to insure the proper category slot; the selection of judges and group leaders along with the film categories to be judged by each group.

His work on the Steering Committee of Black Filmworks (the Annual Film Festival component of BFHF) consisted of curating the film screening selections. During Black Filmworks he moderated the filmmaker question and answer sessions. In order to make available the works of independent Black filmmakers to the public on an ongoing basis he began hosting a popular monthly screening at Geoffrey’s Inner Circle, a landmark event space in Oakland that lasted for 4 years.

Film historian Felix Curtis shines light on the artistic value of the complex Black film canon.

DISCOVERING BLACK FILM CLASSICS

SouthPark Magazine

By Michael Solender

October 20, 2020

Two years after moving to Charlotte from the San Francisco Bay area in 2006, Felix Curtis was itching to bring his love of lesser-known films featuring Black artists and themes to Charlotte audiences.

Curtis came to Charlotte as the longtime curator of the San Francisco Black Film Festival and Black Filmworks, the annual festival component of the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, where he later served as executive director. In 2008, the Classic Black Cinema Series was born, screening the second Sunday afternoon monthly at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American Arts + Culture. (The series has been online during the pandemic.)

SouthPark recently spoke with Curtis, who shared insights on his selection process, race films and contemporary filmmakers to watch.

Comments were edited for brevity.

What criteria do you use to designate a film classic and choose for screening?

It’s the quality and the content of the film. Since launching the series, most films have been in that ’30s to ’60s period. Initially I looked to noteworthy talent like Dorothy Dandridge, Oscar Micheaux, the great Paul Robeson, Josephine Baker and others.

Recently, I’ve been showing the films that have been done in the ’70s. Half or maybe even three quarters of my audience hasn’t seen these films. The older films are the ones that I really gravitate toward, because they highlight actors that people aren’t familiar with or didn’t know existed but were great actors.

You mention Micheaux, why is he so venerated?

He’s identified as the godfather of Black cinema. Modern-day filmmakers like Spike Lee and John Singleton found inspiration in Micheaux. He was a guerrilla filmmaker, making films on small budgets and [with] borrowed material. Two classic Micheaux films I recommend are both silent. Within Our Gates (1920) was a counterpoint to Birth of a Nation (1915). Body and Soul (1925) is a classic because it was Paul Robeson’s first film, and he played two parts.

There was an era (from the ’20s to the ’40s) of what were called “Race Films.” What is their background?

Race films were films [made by Black film companies for Black audiences] that had a predominantly Black cast and predominantly racial themes. There was segregation in the mainstream theaters during this time. These were serious films though, not comedies. They were dramas. There was always this element of the color, of there being either someone passing for white or someone upholding the Black race against those who were trying to degrade the race.

In the ’70s there were Blaxploitation films. These films had a predominantly black cast, though the subject matter was usually that of ‘getting one over on the man.’ Superfly (1972) is a good example. One of my favorites is Willie Dynamite (1973). It was a Blaxploitation film featuring a good-natured pimp. Ironically, the star of this film was one of the original stars of Sesame Street, Roscoe Orman.

What do you find exciting about contemporary Black film?

Female filmmakers are showing what they’re capable of. Ava DuVernay is spearheading that whole genre of positive image, love stories — dealing with things other than race, dealing with relationships. Ryan Coogler is doing great things. Black Panther (2018) is a culmination of his prior great work. Fruitvale Station (2013) was great. Many actors are getting into directing now. Regina King is doing great work acting and directing, and Spike Lee is still producing Spike Lee movies. Hollywood is not the epicenter of quality films. Independent films are now dominating as far as the quality, and audiences are responding.

![Film historian Felix Curtis shines light on the artistic value of the complex Black film canon. DISCOVERING BLACK FILM CLASSICS SouthPark Magazine By Michael Solender October 20, 2020Two years after moving to Charlotte from the San Francisco Bay area in 2006, Felix Curtis was itching to bring his love of lesser-known films featuring Black artists and themes to Charlotte audiences. Curtis came to Charlotte as the longtime curator of the San Francisco Black Film Festival and Black Filmworks, the annual festival component of the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, where he later served as executive director. In 2008, the Classic Black Cinema Series was born, screening the second Sunday afternoon monthly at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African American Arts + Culture. (The series has been online during the pandemic.) SouthPark recently spoke with Curtis, who shared insights on his selection process, race films and contemporary filmmakers to watch. Comments were edited for brevity. What criteria do you use to designate a film classic and choose for screening? It’s the quality and the content of the film. Since launching the series, most films have been in that ’30s to ’60s period. Initially I looked to noteworthy talent like Dorothy Dandridge, Oscar Micheaux, the great Paul Robeson, Josephine Baker and others.Recently, I’ve been showing the films that have been done in the ’70s. Half or maybe even three quarters of my audience hasn’t seen these films. The older films are the ones that I really gravitate toward, because they highlight actors that people aren’t familiar with or didn’t know existed but were great actors. You mention Micheaux, why is he so venerated?He’s identified as the godfather of Black cinema. Modern-day filmmakers like Spike Lee and John Singleton found inspiration in Micheaux. He was a guerrilla filmmaker, making films on small budgets and [with] borrowed material. Two classic Micheaux films I recommend are both silent. Within Our Gates (1920) was a counterpoint to Birth of a Nation (1915). Body and Soul (1925) is a classic because it was Paul Robeson’s first film, and he played two parts. There was an era (from the ’20s to the ’40s) of what were called “Race Films.” What is their background? Race films were films [made by Black film companies for Black audiences] that had a predominantly Black cast and predominantly racial themes. There was segregation in the mainstream theaters during this time. These were serious films though, not comedies. They were dramas. There was always this element of the color, of there being either someone passing for white or someone upholding the Black race against those who were trying to degrade the race. In the ’70s there were Blaxploitation films. These films had a predominantly black cast, though the subject matter was usually that of ‘getting one over on the man.’ Superfly (1972) is a good example. One of my favorites is Willie Dynamite (1973). It was a Blaxploitation film featuring a good-natured pimp. Ironically, the star of this film was one of the original stars of Sesame Street, Roscoe Orman. What do you find exciting about contemporary Black film? Female filmmakers are showing what they’re capable of. Ava DuVernay is spearheading that whole genre of positive image, love stories — dealing with things other than race, dealing with relationships. Ryan Coogler is doing great things. Black Panther (2018) is a culmination of his prior great work. Fruitvale Station (2013) was great. Many actors are getting into directing now. Regina King is doing great work acting and directing, and Spike Lee is still producing Spike Lee movies. Hollywood is not the epicenter of quality films. Independent films are now dominating as far as the quality, and audiences are responding.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58b9d22b414fb53851181956/1610232723988-HAOR7J43AJG31IH1GU8B/Felix+Curtis-4.jpg)